AuthCodeFix aka ConsentFix

Just before year's end, ConsentFix emerges: a clever OAuth-based attack that abuses legitimate authentication flows to steal the authorization code, effectively handing attackers the keys to Microsoft Entra. We break down why this works despite Conditional Access, which signals it leaves behind in the logs, and how defenders can detect and stop it before real damage is done.

As it is tradition right before the end of the year, a new vulnerability or clever attack vector appears, and Defenders are left trying to protect their users. Meanwhile, other attackers and red teamers watch closely and adapt.

This year, PushSecurity detected an attack that they named "ConsentFix", an evolution of the ClickFix attack that relies on the user to provide the attacker with a URI that basically hands over the key to the Entra kingdom. The method used in the wild relied on a manual copy and paste action by the user to work. Within a few days, John Hammond released a video demonstrating an improved version of the attack that no longer required copy and paste, instead, the user could simply drag and drop their auth code to the attacker.

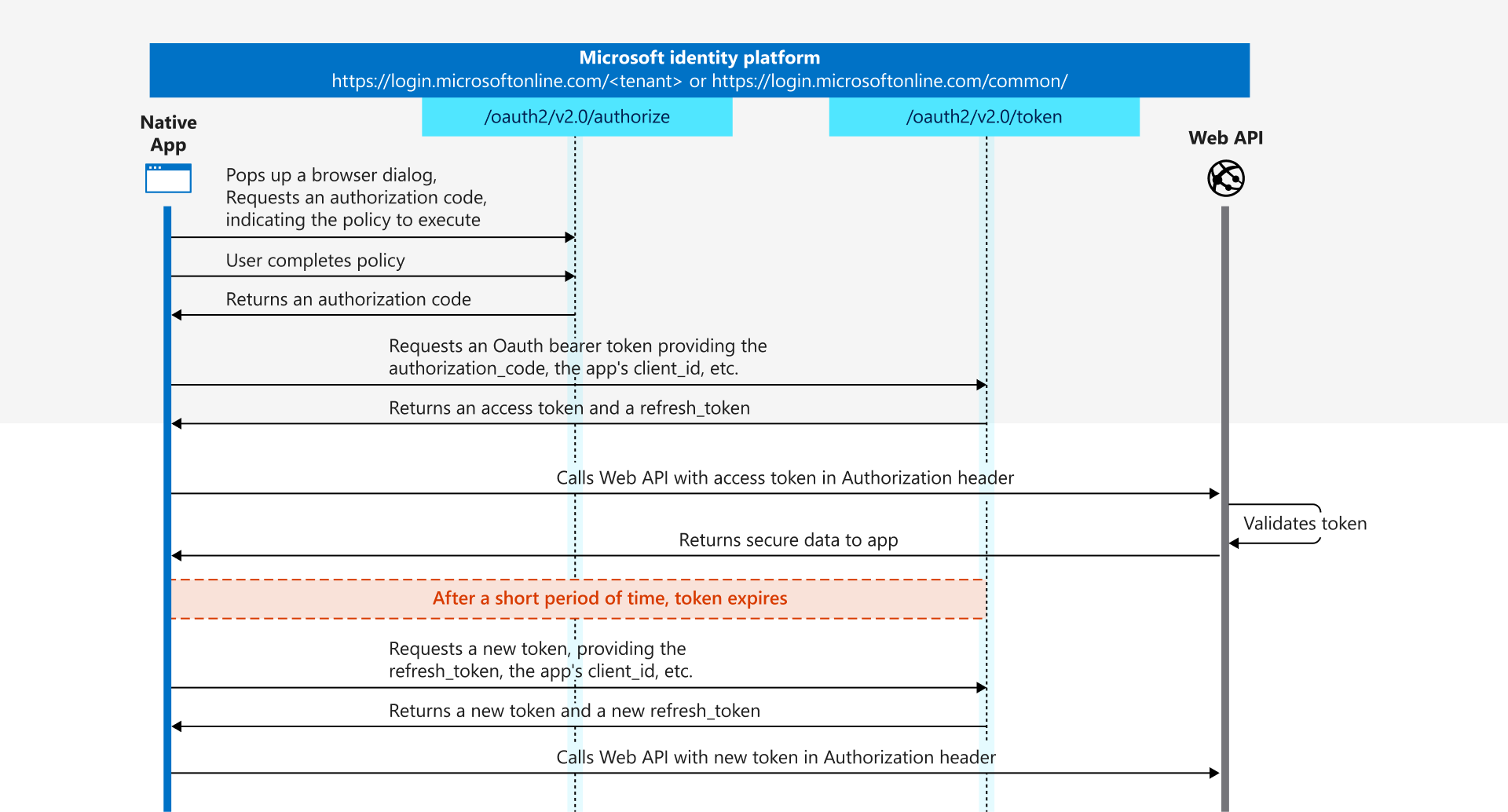

When we look into the technical details of why this attack works and seemingly bypasses device compliance and other Conditional Access requirements, we find ourselves in the OAuth 2.0 authorization code flow.

The attacker creates a Microsoft Entra login URI that targets the "Microsoft Azure CLI" client and the "Azure Resource Manager" resource, and opens this URI when the user visits the malicious website.

Mapped to the authorization code flow, this corresponds to the first step that a native public app such as the Azure CLI would normally call to authenticate the user. The application creates a listener on the machine on which it is executed, on a random high port. This port is used as a so called reply URI.

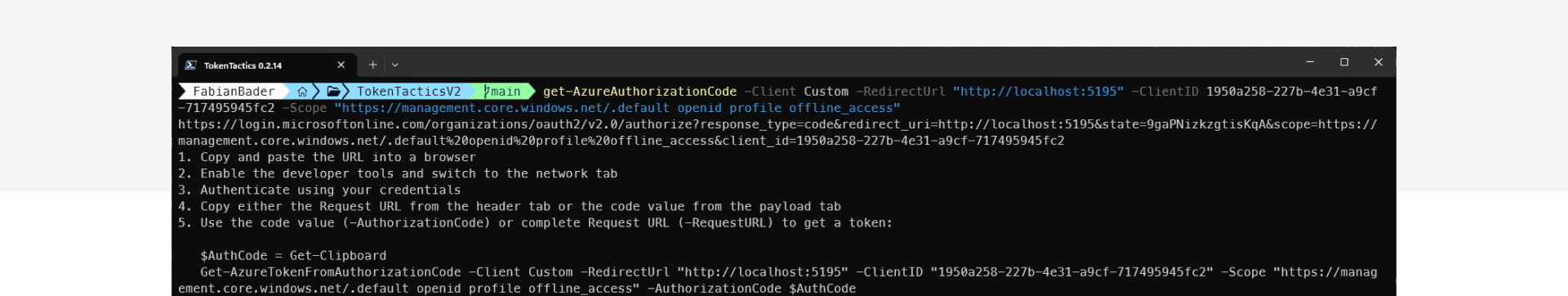

You can easily reproduce this yourself, for example by using TokenTacticsV2, or by crafting the URI manually.

After the user successfully signs into Entra ID, the user is redirected to the reply URI, e.g., http://localhost:3001. In a normal scenario, the Azure CLI would now accept the call to this URI and would receive the important and critical information that is part of the redirect:

- code

This is the authorization_code, which the application uses to request a bearer token, which consists of access, ID, and optionally the refresh token.

According to the documentation, this code is valid for around 10 minutes and must be redeemed within this time. - state

This is an optional parameter, and the application should verify whether it is identical in the request and response.

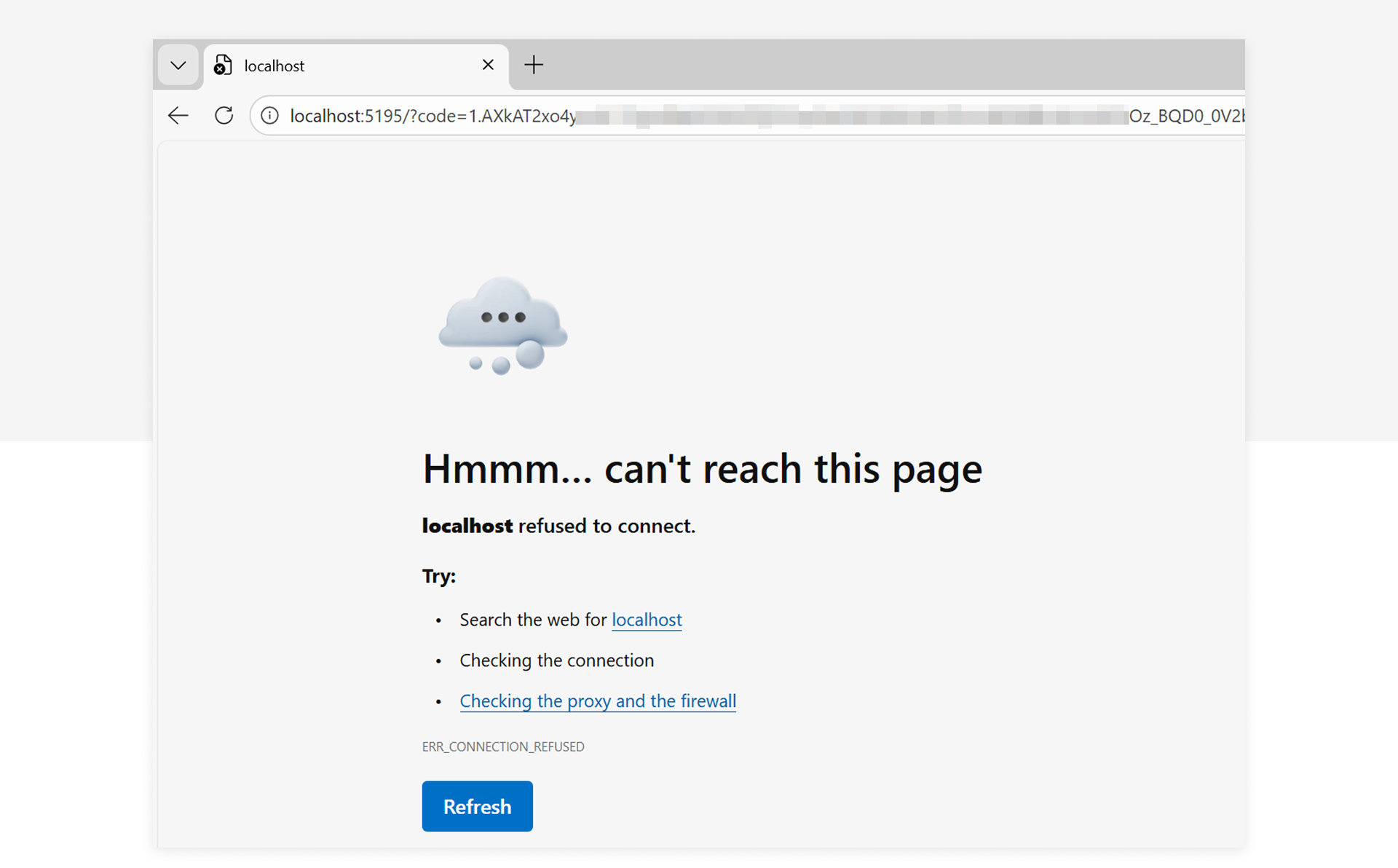

In the attack scenario, the user is also redirected, but since no application is running on localhost, the browser encounters an error.

But the URI still contains the sensitive information and this is what the attacker wants the user to provide them. If the user obliges the attacker will now redeem the token material and can then use the access and refresh token to access the resource, in this case Azure Resource Manager.

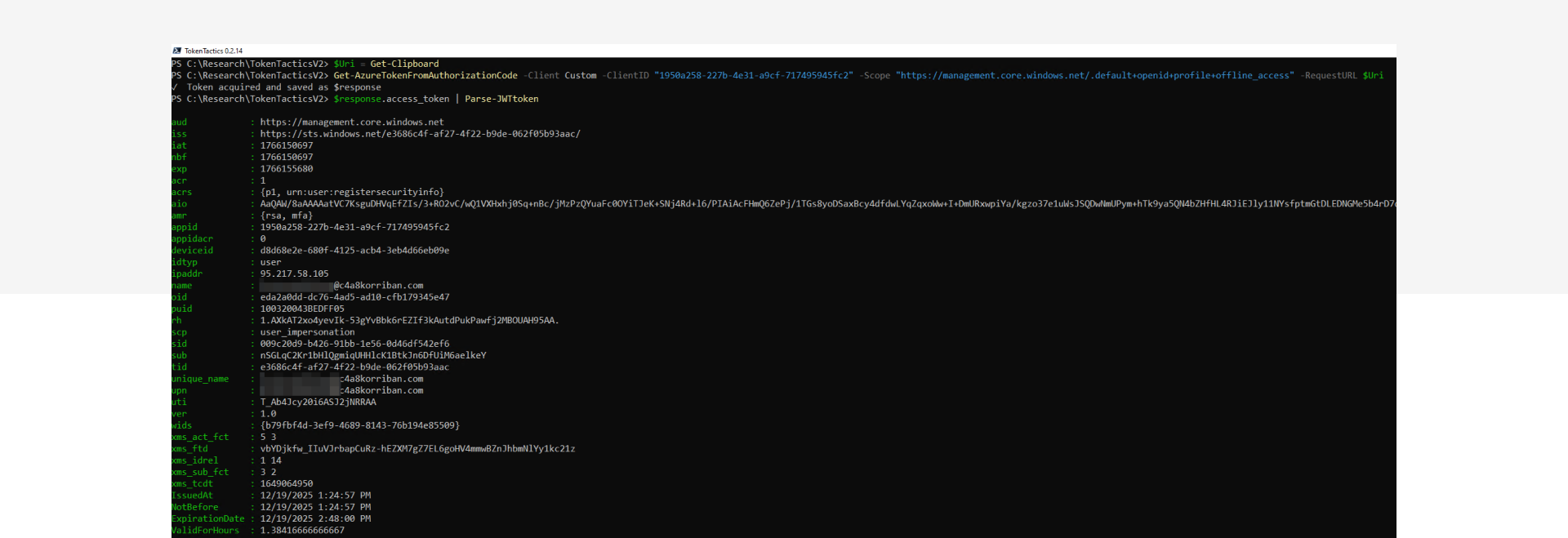

In this screenshot you will see how to retrieve the bearer token using the URI provided by the user.

If you want to test your detections, make sure you execute the last step from a different system, in a different network.

Detection artifacts

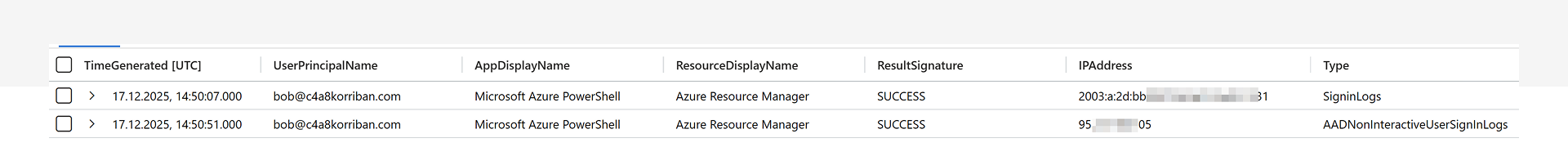

When you reproduce the attack and check the SigninLogs and AADNonInteractiveUserSignInLogs, you'll see two events for this single sign-in activity. The first event represents the actual user sign-in, while the second originates from the attacker's infrastructure.

The big difference is that the first event is an interactive sign in event, while the second is non-interactive. This translates to the two stages of the authentication flow: first the user, then the application or in our case the attacker.

Regular behavior of the Azure CLI would be that both sign-in events originate from the same IP address. However, in our case the IP addresses are different, and they originate from different countries. Of course, the latter is not a reliable indicator, as the attacker could reside in the same country as the victim to hide their tracks.

Missing link

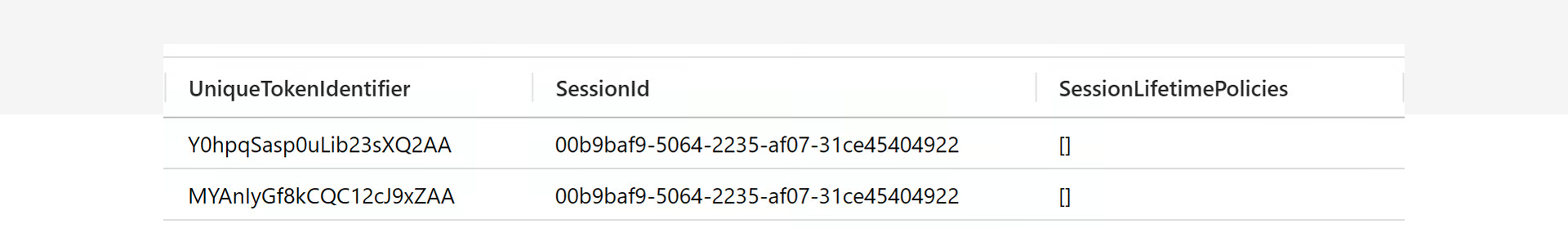

When looking for a good way to link those two events, the natural first idea was to check the Unique Token Identifier (UTI). However, Microsoft uses different values for the authorization code UTI and the bearer token UTI, so this approach doesn't work as a reliable link.

However, the SessionId is a good link between the two, though it is a long-running ID and might contain multiple of these event combinations, even legitimate ones.

With the additional knowledge of the auth code flow limitations and the user and application id as additional links you can use time as an important detection factor:

- Both events share the same SessionId

- Both events share the same ApplicationId

- Both events share the same UserId

- The second event must be after the first event

- The second event must be within approximately a 10-minute time window after the first event. You should not use exactly 10 minutes as Microsoft writes "[...] they expire after about 10 minutes"

- You should only consider the very next second event, not subsequent ones

Fun fact

The ResourceIdentity is not a good link, as the attacker can change the resource since it is not bound to the auth code. The targeted application ID cannot be changed.

Reduce the noise

This knowledge already provided us with a good working detection, but there were benign positives in the mix as well. Modern developers use cloud resources that appear like local instances, but result in irregular login patterns in the logs.

The key difference is the time component. While the attack requires user interaction to copy and paste or drag and drop the URI, the GitHub Codespace use case we identified as the source of the benign positive alerts is completely automated and redeems the auth code within mere seconds.

So filtering out anything that does this authentication dance within a few seconds can most likely be removed as benign.

Another source of noise could be changing egress points for your internet traffic, especially in SD-WAN, ZTNA or Secure Web Gateway scenarios.

Affected first-party applications

While the initial report shows "Microsoft Azure CLI" as the abused application there are a lot of different Microsoft first-party apps with pre-consent in every tenant that offer localhost as redirect. And not only those are a target. The attacker could also abuse reply test and dev URLs that are not publicly resolvable.

Here is a list of the most notable applications that also have high pre-consentet permissions on resources.

- Microsoft Azure CLI (04b07795-8ddb-461a-bbee-02f9e1bf7b46)

- Microsoft Azure PowerShell (1950a258-227b-4e31-a9cf-717495945fc2)

- Visual Studio (04f0c124-f2bc-4f59-8241-bf6df9866bbd)

- Visual Studio Code (aebc6443-996d-45c2-90f0-388ff96faa56)

- MS Teams PowerShell Cmdlets (12128f48-ec9e-42f0-b203-ea49fb6af367)

A full list of these apps are now included in EntraScopes.com by our colleague Fabian Bader.

Mitigations and Protections

Limit the attack surface and audience

Mitigation: Medium (reduces the potential audience for the attack)

Scope: limited

Option 1: Require User Assignment

Pre-requisites:

- Add the service principal for affected first-party apps by using Microsoft Graph API or PowerShell

- Apply the user assignment requirement on the service principal object using Microsoft Graph API or PowerShell

- Establish a process to assign users upon request via Access Packages, PIM-for-Groups (for just-in-time access), or a combination of both.

// Example for Microsoft Graph PowerShell

Connect-MgGraph -Identity

$AppId = "04b07795-8ddb-461a-bbee-02f9e1bf7b46" // Microsoft Azure CLI

$sp = Get-MgServicePrincipal -Filter "appId eq '$AppId'"

Update-MgServicePrincipal -ServicePrincipalId $sp.Id -AppRoleAssignmentRequired:$false

Benefit:

- Enables management of user assignments through Access Packages or manual group membership to limit exposure to this attack technique.

- Option to provide just-in-time access combined with eligible group membership assignment, allowing temporary access to CLI tools and thereby further reducing the attack surface.

- Applied before evaluating Conditional Access policies.

- Limits the attack surface for other scenarios as well.

Disadvantage:

- Can only be scoped to specific users and not combined with other requirements like usage of specific devices

- All legitimate CLI tool users must be identified

- Side effects and organizational impact must be carefully assessed by reviewing previous sign-ins.

Option 2: Block access by using Conditional Access Policies

Pre-requisites:

- Create a Conditional Access policy to block access to CLI tools, excluding legitimate users, by targeting "Microsoft Graph Command Line Tools" and "Windows Azure Service Management API"

- Manage exclusions via group membership, either manually or through entitlement management (e.g., Access Packages).

Benefit:

- Prevents token issuance for non-legitimate or non-privileged users.

- Allows granular scoping based on additional conditions such as device or network.

Disadvantage:

- All legitimate CLI tool users must be identified and excluded.

- Side effects and organizational impact must be carefully assessed by reviewing previous sign-ins and evaluating the policy in report-only mode.

Block token issuance by authorization code flow

Deployment effort: High

Mitigation: High

Scope: Very limited

Pre-requisites:

- Microsoft Entra ID P1 licenses

- Entra ID Registered Devices, Hybrid or Entra ID-joined devices on Windows platform

- Enable Web Account Manager (WAM) in Azure CLI, Azure PowerShell and Microsoft Graph PowerShell (default in latest versions)

- Configure Conditional Access targeting:

- Cloud App targeting to the following apps:

- Office 365 Exchange Online

- Office 365 SharePoint Online

- Microsoft Teams Services

- Client apps under Mobile apps and desktop clients to require Token Protection.

- Select Windows as device platform for targeting the policy

- Cloud App targeting to the following apps:

Benefit:

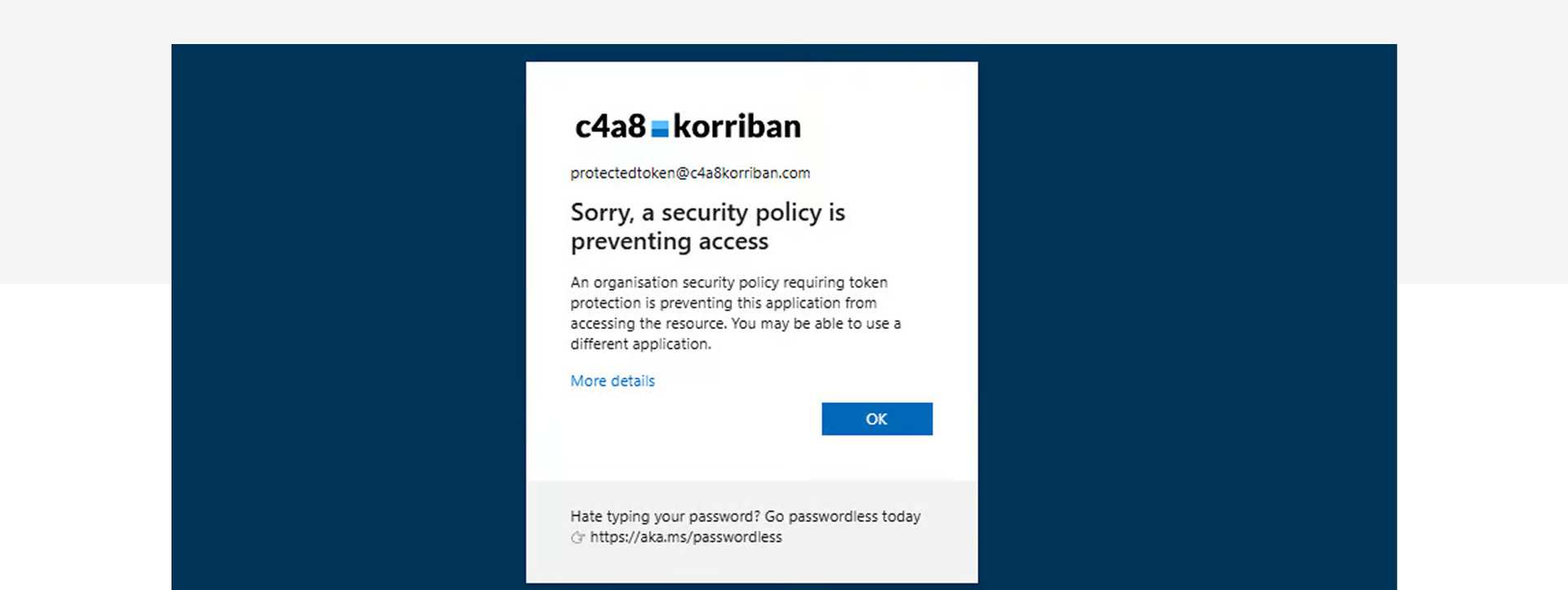

Microsoft Entra’s token protection requires proof‑of‑possession (PoP), which can only be enforced when the client communicates directly with a trusted token broker such as the Web Account Manager (WAM) on Windows. Because browsers cannot establish this secure channel, the authorization code flow initiated in a browser is blocked under token protection policies.

When the policy enforces token protection that requires broker‑managed PoP, the authorization code returned to a browser cannot be redeemed because the browser cannot produce the required broker‑signed proof during the code to token exchange

In this case, attacks with AuthCodeFix will be fully mitigated as long the application can be protected by Token Protection.

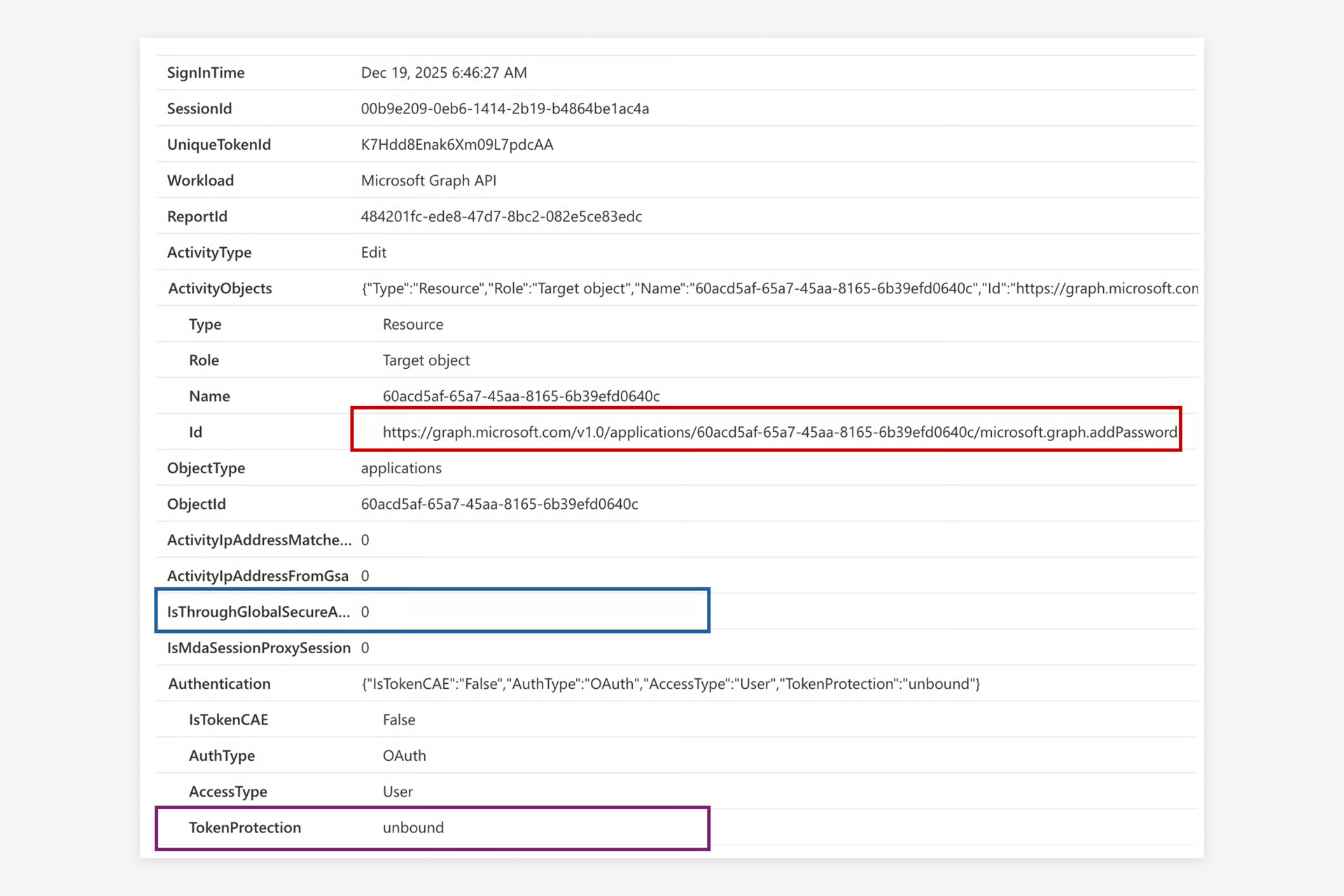

As shown in the screenshot below, Token Protection successfully mitigates the redemption of the authorization code flow initiated by the victim through a phishing action.

Disadvantage:

- Only the following resources are officially supported:

- Office 365 Exchange Online

- Office 365 SharePoint Online

- Microsoft Teams Services

The Microsoft Graph API is indirectly covered by the previously mentioned resources and Microsoft Graph PowerShell is listed as a supported client. We were able to verify in our testing that the attack for this scenario will be mitigated. “Windows Azure Service Management API" is not listed as a supported resource. Both CLI clients (Azure CLI and Azure PowerShell) support WAM which is a client-side requirement to use Token Protection. Microsoft has been announced in a blog post to extend token protection capabilities for Azure management scenarios.

- Some bugs in Microsoft Graph PowerShell force you to temporarily disable WAM integration

- Side effects and organizational impact must be carefully assessed by reviewing previous sign-ins and evaluating the policy in report-only mode. The cloud app targeting will also effect productivity access to Microsoft 365.

- Limited scope due to availability on supported platforms and Entra ID–integrated devices.

Block further token issuance by compliant network check or trusted network

Mitigation: Medium

Scope: Broad

Option: Block access outside of Compliant network with Global Secure Access

Pre-requisite:

- Entra ID P1 license

- Entra ID Registered Devices, Hybrid or Entra ID-joined devices on Windows, macOS, Androind and iOS platform

- Global Secure Access Client on all affected clients and enabled Entra Internet Access for M365 Traffic Profile

- Conditional Access Policy to enforce network compliant check should be applied to all cloud apps

Benefit:

Block additional token issuance by enforcing a trusted network check. This mitigation ensures attackers cannot obtain new tokens using the refresh token from the authorization code flow. However, it does not prevent the initial redemption of the authorization code or the issuance of the first access token, which remains valid outside the compliant network because it was originally requested by the victim.

Enforcing GSA with the Compliant Network condition also blocks other Token Replay scenarios and adds additional logs which can be very useful for detections and hunting.

Disadvantage:

- Only applicable for users and devices with deployed Global Secure Access client

- Limited scope due to availability on Entra ID–integrated devices

- Enforcing Compliant Networks via CA will need some Exclusions like Intune to avoid chicken-egg-problems. Detailed testing is needed before rollout

Hunting queries

Once all the prerequisites for token theft mitigations are met - such as deploying the GSA client (including ingestion of NetworkAccessTraffic logs) and taking benefit of WAM authentication - we gain additional options for threat hunting and verification.

Leveraging GSA Logs and WAM Authentication for hunting or verify confidence on detection results

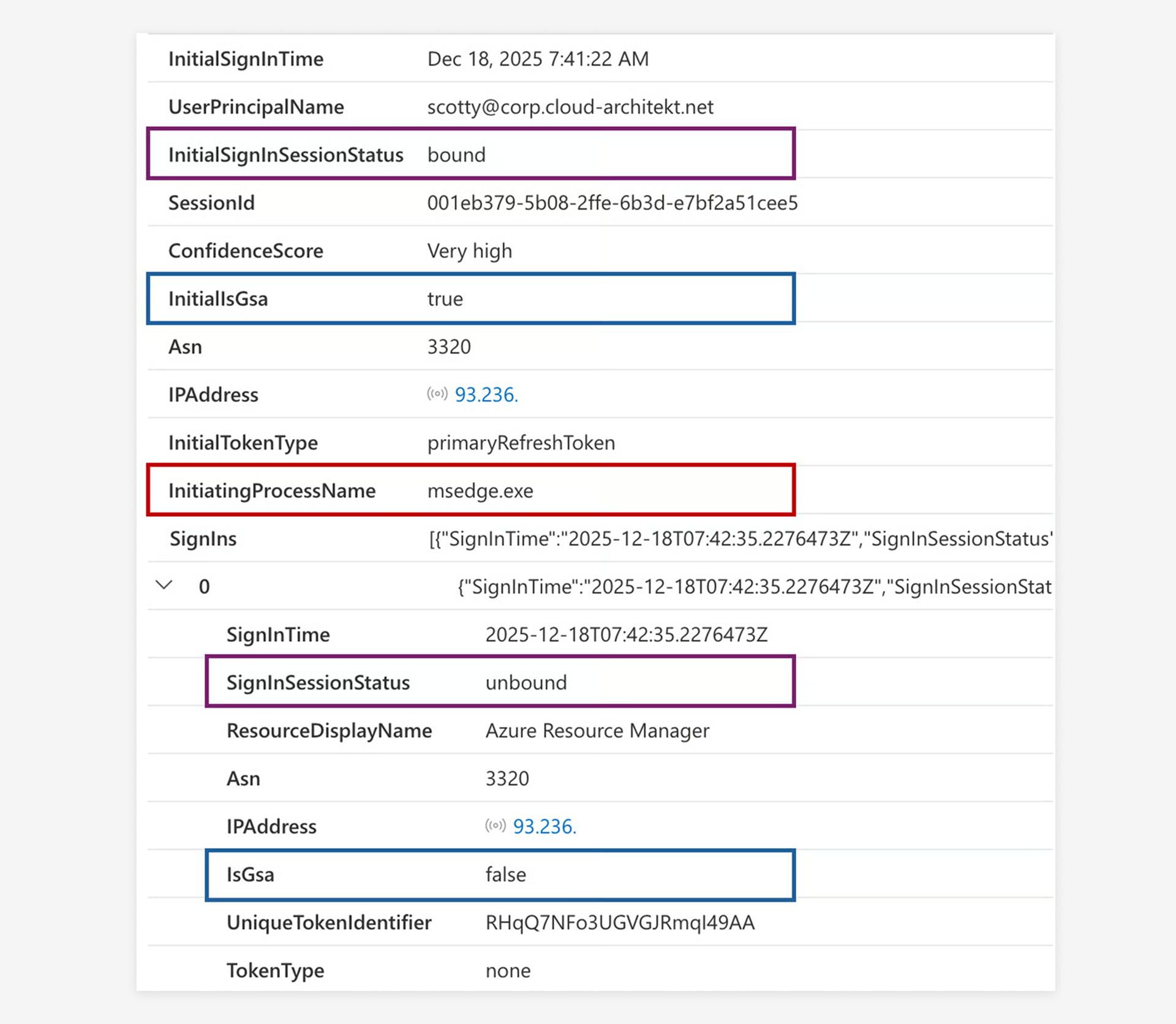

This hunting query leverages NetworkAccessTraffic logs from Global Secure Access (GSA), which include the initiating process for communication with the Microsoft Entra token endpoint. This helps determine whether a token request originated directly from a browser and also whether any additional token requests were made outside the GSA network.

This query works and delivers only reliable results when the prerequisites are met; otherwise, it leads to a high false-positive rate.

Why this matters: When signing in via CLI or PowerShell modules using Web Account Manager (WAM) on Windows Devices, the flow does not involve a browser-based authorization code. This sign-in behavior is the default in the latest version. Therefore, if the initiating process is a browser executable (e.g., msedge.exe), this is a strong indicator of suspicious activity. On macOS, the process is initiated by the Company Portal app (com.microsoft.CompanyPortalMac.ssoextension) when using Platform SSO.

Token Binding and PoP: WAM authentication typically binds tokens to the device by enforcing Proof-of-Possession (PoP). Attackers cannot issue further bounded tokens without PoP, so an unbounded refresh token is another strong indicator.

Limitations: All the mentioned signals are only available when the accessing device is registered with or joined to Microsoft Entra ID.

Confidence Score Logic: The query combines multiple signals to calculate a confidence score:

- Presence of a browser process initiating token requests.

- Detection and down grade to unbounded tokens.

- Network provider changes (including Compliant to non-compliant) between sign-ins.

These signals can be used in the query to hunt for activity or to derive a confidence score in the event of an incident based on the previous detection.

The following scoring will be shown depending on the conditions:

A very high confidence score is displayed when NetworkAccessTraffic logs indicate a familiar browser process instead of initiating a token request, and a downgrade of an unbound token has been detected.

A high confidence score is shown when the sign-in occurs from a different Network Provider (ASN) and a non-compliant network involving unbound tokens.

A medium confidence score is shown when only a change in Network Provider and compliant network is identified, along with a change in the token type used.

You’ll find the latest version of the hunting query on GitHub.

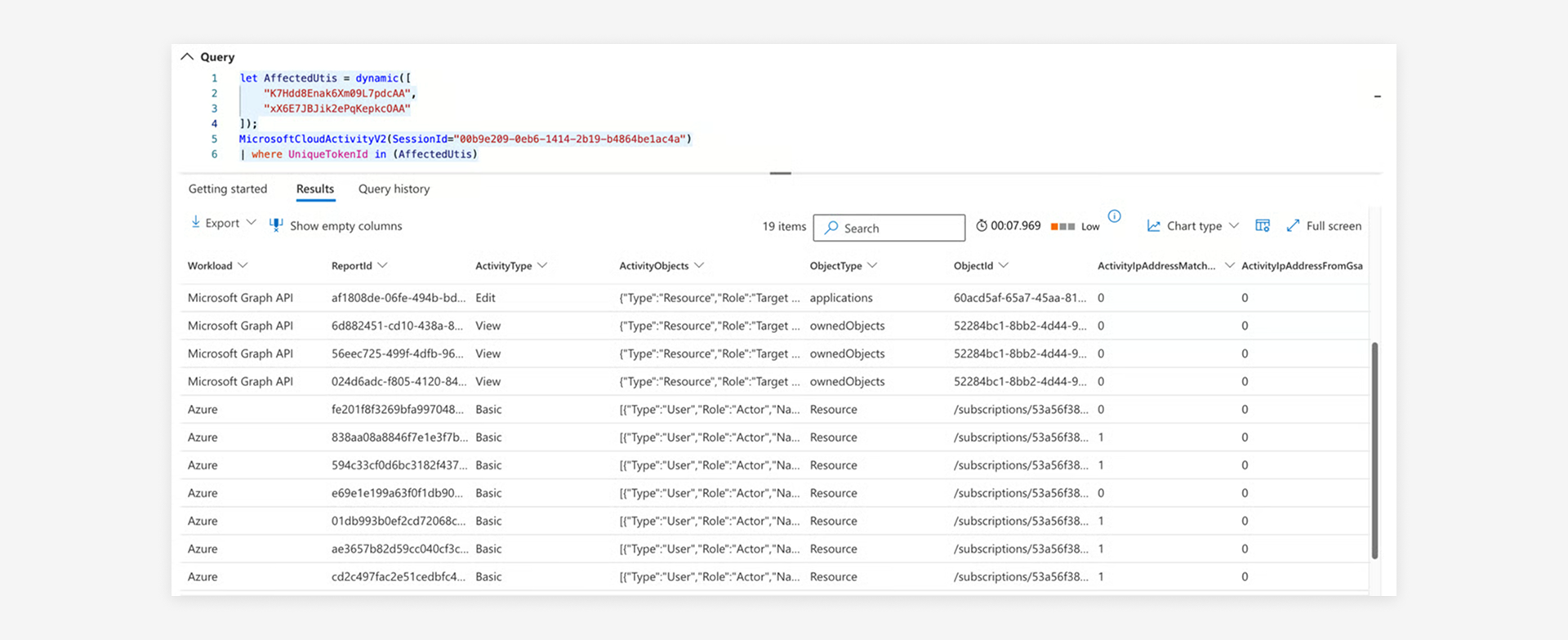

Hunting for activities by issued tokens

You should consider expanding your investigation beyond sign-in events to include activities performed using tokens issued by the attacker. Our colleague Thomas Naunheim has published a KQL function called MicrosoftCloudActivity, which can assist in this extended hunting process. Additionally, the affected SessionId can be correlated with suspicious UniqueId values identified during previous hunts for deeper analysis.

In this example, the attacker leveraged the refresh token obtained during the attack to issue an access token for the Microsoft Graph API. This token was then used to maintain persistent access and lateral movement by adding a client secret to an application owned by the victim. The query provides details about the Graph API operation, including the token protection status and whether the operation occurred outside the Global Secure Access network.